Kochi | A collaborative Indo-German research team has identified a clear biological mechanism linking disturbances in gut bacteria to impaired memory, learning, and cognitive function, CUSAT said on Thursday.

The study, published in the latest issue of 'BMC Biology', demonstrates how disruption of the gut microbiome—commonly triggered by prolonged antibiotic use or dietary imbalances—initiates systemic inflammation that ultimately affects the neural circuits responsible for memory formation, CUSAT said in a statement.

'BMC Biology' is an open-access scientific journal publishing original, peer-reviewed research across all fields of biology.

The research was conducted under a program supported by the Department of Science and Technology (DST) and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD).

The team was led by Dr Baby Chakrapani PS from the Centre of Excellence in Neurodegeneration and Brain Health (CENABH) and the Centre for Neuroscience, Department of Biotechnology at Cochin University of Science and Technology, and Prof Martin Korte from the Technical University of Braunschweig and the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI).

The research was carried out as part of Krishnapriya's doctoral research under the supervision of Chakrapani.

CUSAT's statement explained that researchers examined how antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis—an imbalance in the gut microbial community—impacts physiological processes beyond the intestine.

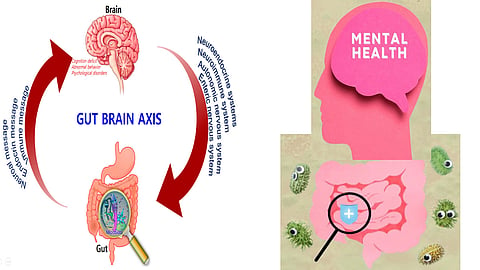

Their findings reveal that disturbances in gut bacteria trigger a cascade of inflammatory and oxidative responses that compromise the integrity of the gut barrier, generating signals that reach the brain and alter its immune environment.

"Gut dysbiosis initiates a systemic inflammatory state that does not remain confined to the gut. These inflammatory cues eventually influence the brain's own immune cells," Chakrapani said.

A crucial observation concerned the behaviour of microglia, the brain's resident immune cells, which act as custodians by removing cellular waste and pruning weak or unnecessary synapses—the junctions through which neurons communicate.

Under sustained gut-derived inflammatory stress, microglia became overactive, removing not only weak synapses but also healthy neural connections essential for memory formation.

"Instead of selectively refining synapses, they began removing critical neural connections involved in forming and storing memories. This excessive pruning led to observable difficulties in learning and memory tasks," Korte said.

The researchers emphasised that gut dysbiosis is increasingly common due to frequent antibiotic use, highly processed diets, stress, and poor sleep—factors that reduce gut microbial diversity.

"People often think of gut health only in relation to digestion," Korte said, adding, "But our results show that maintaining a healthy gut environment is also essential for cognitive well-being." According to CUSAT, the findings open new avenues for interventions, suggesting that safeguarding gut health through prudent antibiotic use, targeted probiotics, and a balanced diet may not only protect the digestive system but also actively preserve cognitive functions.

"We are only beginning to understand how deeply connected the gut and brain really are. This study is one step towards mapping that complex relationship," Chakrapani said.

The team expects future studies to explore whether restoring gut balance could reverse cognitive deficits and whether similar mechanisms are involved in neurodegenerative disorders.