Ajayan

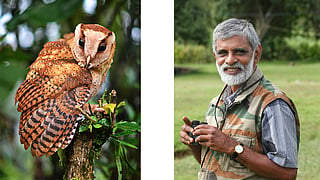

As one enters the Interpretation Centre at Thattekkad Bird Sanctuary, described by renowned ornithologist Salim Ali as the richest bird habitat in peninsular India, two things immediately catch the eye: a mural of the 'birdman' himself and an image of the rare Ripley Owl. Both these features have fascinating stories behind them, as revealed by R Sugathan, an ornithologist and disciple of Salim Ali who spent over 18 years with his mentor.

In the early 1970s, Sugathan, along with former chairman of the Kerala State Biodiversity Board VS Vijayan and Razakh Khan, a Bangladeshi student of Salim Ali, were on a trek through the enchanting forests of Parambikulam. Amidst their journey, they paused to quench their thirst, only to stumble upon a group of children engrossed in a game with an owl, its legs cruelly bound.

Razakh, deeply disturbed by this sight, promptly intervened and took the owl. With their hearts set on restoring the bird to its natural habitat, they carried it in a bag with hopes of releasing it back into the wild. However, fate had a different plan. Upon reaching Thellikkal, they discovered that the bird had succumbed to its ordeal. Undeterred, they decided to preserve its memory, carefully stuffing the owl and sending it to the Bombay Natural History Society, under the leadership of Salim Ali.

During his weekly visit to the BNHS, Salim Ali was presented with the latest specimen. Upon close inspection, he realized that it was a bird not commonly encountered. Expressing his dissatisfaction with the less-than-ideal taxidermy work, he chided Sugathan, who recounted the circumstances of its discovery. Salim Ali then told Sugathan to embark on a detailed examination of the bird, scrutinizing its hues and distinctive features.

After sharing their findings with institutions such as the British Museum, it was confirmed that the owl belonged to a previously undocumented sub-species. This groundbreaking discovery, however, required several years of meticulous study before a conclusive identification could be made. Once this milestone was reached, the time came to christen the newfound species.

While there were suggestions to name the owl after Salim Ali, the ornithologist declined, citing the numerous other species already bearing his name. Eventually, it was decided to dedicate the owl to S Dillon Ripley, the then director of the Smithsonian Institute and Salim Ali's co-author for the 'Handbook of Indian Birds'.

Sugathan's legacy in Kerala's ornithological annals is indelible, notably through the establishment of interpretation centres at Parambikulam and Thattekkad. The genesis of these centres can be traced back to his expeditions with Salim Ali, where the seeds of the idea were sown. It basically is to create a micro-habitat and explain things to visitors.

Recalling his evenings spent with Salim Ali at Kuriyarkutty in Parambikulam, Sugathan proposed the idea of a centre to the birdman. Following Salim Ali's return to Mumbai, Sugathan wasted no time in approaching Kerala's forest department officials. Encouraged by the supportive response from top officials, including the then Chief Conservator of Forests Surendranath Assari, Sugathan was instructed to proceed with the plan, specifically at the location where Salim Ali used to reside in Parambikulam.

The foundation was laid, but Sugathan's demanding role as a scientist for BNHS’ bird migration project, which required him to traverse the length and breadth of India, left him with little time to oversee the centre’s progress. This, coupled with the financial constraints that plagued the initiative, led to further delays in commencing the construction work.

Sugathan fondly reminisces about Salim Ali's final visit to Parambikulam around 1985. Salim Ali was conferred with a doctorate by Tamil Nadu Agriculture University and Sugathan helped him read the speech. After the ceremony, Sugathan and his mentor travelled to Palakkad and conducted a survey for a bird sanctuary near Malampuzha dam. Invariably, Parambikulam was on Salim Ali’s agenda and the duo drove in Sugthan’s car. During their visit to Kuriyarkutty, Salim Ali, gazing upon the foundation of the interpretation centre, inquired if the project would be completed within his lifetime. An optimistic Sugathan assured him that it would be swiftly accomplished, revealing that even the forest department had envisioned a tranquil retirement for him amidst the serene wilderness, far removed from the urban chaos of Mumbai. Tragically, fate intervened and the birdman died after two years.

Despite being unable to personally oversee the construction, Sugathan's vision for the interpretation centre at Parambikulam materialized into a concrete structure, a departure from the initial concept. Undeterred, Sugathan pushed forward, and the centre was successfully established, a testament telling the story of Parambikulam through its natural wonders such as the awe-inspiring Kannimara teak, the tallest living tree in the area at nearly 48 meters.

Navigating between Parambikulam and Thattekkad, Sugathan embarked on establishing an interpretation centre at the latter as well. Supported by the then CCF TM Manoharan, who passed away very recently, Sugathan's vision took shape outside his office, where Manoharan proposed joining two offices to create a spacious hall on the first floor. Sugathan swiftly acted on this idea, resulting in the establishment of the Thattekkad centre. The story of Thattekad is revealed through the owl and as respect for Salim Ali, a mural of his was put up and an image of the owl too.

Sugathan's empathetic nature extends to engaging with the local community, particularly children, to learn about their observations of birds and plants. This approach has led to heartwarming instances where children, like one in Thattekkad, brought injured birds to his attention. One such case involved a young boy discovering a little owl by the roadside, injured from attacks by crows. This marked the second encounter with a Ripley Owl for Sugathan. Taking swift action, he collaborated with the then ranger Ouseph to nurse the owl back to health. They housed the owl in a spacious cage by Sugathan's office window, where he diligently fed it meat to aid its recovery.

In 1992, a newspaper report highlighted Sugathan's encounter with a Ripley Owl, prompting a rubber tapper near Pala to contact him. The rubber tapper had been caring for a similar owl and, recognizing its rarity, wanted Sugathan to take it. Without delay, Sugathan and the ranger journeyed to Pala and brought the owl to Thattekkad. Sugathan remembers that there was a difference in hue. Despite initial concerns about potential aggression between the two owls, the two got together well. The twist came when one morning Sugathan was surprised by their engagement in courtship. This behaviour revealed that the newcomer from Pala was a female, explaining the slight difference in hue compared to the male owl already in Sugathan's care.

Not knowing about the nesting practices of owls and their food habits when nursing little ones, Sugathan decided to set them free. There is a flourishing colony of Ripley Owls in the area, he says with excitement.

Sugathan, hailing from an agricultural family in Thanipuzha near Kalady, showed an early interest in mechanics and electronics as a schoolboy, assembling items received from Delhi by VPP. His life took a remarkable turn when, as an undergraduate, he read an article in Science Today with a cover illustration of a pair of birds flying and below an old man looking at them through his binoculars. One bird tells the other that they are flying over India and advises the other to be careful as the old man is watching them. Below the illustration it is mentioned: Interview with the Birdman of India in inner pages. This generated an interest in Sugathan and he read the whole interview which said ornithology is for gaining knowledge. At the end Salim Ali says that those interested in the subject can contact him and his official address and the residential one at Pali Hills were given. That was end to mechanics and electronics for Sugathan who immediately sent a postcard to Salim Ali expressing his eagerness to join him. The reply advised him to complete his graduation first.

After graduation the next year, Sugathan contacted Salim Ali again, and this time, he received an invitation to Mumbai. However, lacking the means to travel, he informed Salim Ali of his predicament. Showing his kindness, Salim Ali sent Sugathan a third-class train ticket. Without informing his parents and having never ventured beyond Ernakulam district, Sugathan embarked on a journey to Mumbai to meet Salim Ali way back in 1972, a decision that would give wings and shape to his future.

Sugathan vividly recalls the lively discussions and travels with Salim Ali, including the birdman's insights into Parambikulam. Salim Ali spoke passionately about the area, mentioning its historical tramway that once connected it to Chalakudy. Even today, remnants of the tramway's can be spotted at certain locations.

Salim Ali also shared anecdotes about the rain shadow forests of Tamil Nadu, situated on the eastern slopes of the Western Ghats, where teak and rosewood trees were once abundant. Their growth was slow and the veneer was excellent. During the British era, these valuable trees were felled and transported to Britain. A strategic high point was chosen, and the timber from the Tamil Nadu side was transported to this point using bullocks and horses. From there, the logs were rolled or slipped down to the tramway terminal on the western side, giving rise to the term ‘top slips’ across forests.

When the Parambikulam dam was constructed, the terminals of the tramway were submerged under water. However, the bungalows that would have been inundated were relocated to higher ground and continue to serve as guest houses for the forest department, preserving a piece of history amidst the changing landscape.

Sugathan, now 74 years old, remains active and engaged in various pursuits. While he may not be directly involved in forest activities, he continues to impart knowledge through classes at Thattekkad and other locations. Additionally, he is actively involved in farming. Sugathan's impact as a mentor is evident, with many of his students achieving their PhDs, while others regularly seek his guidance. An accomplished author, Sugathan has written several books and a few years ago undertook the revision of his mentor's seminal work, Birds of Kerala.